CHAPTER 4: RECOGNIZING THE NAMES OF NOTES IN NOTATED MUSIC

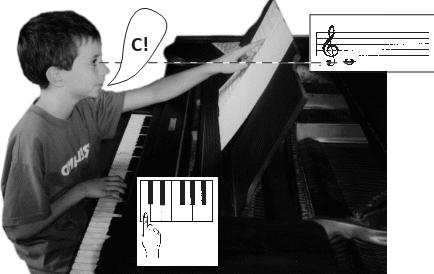

It is time to learn how to recognize the names of the notes in notated music. At first, this recognition process may seem slow. You recognize the note, name it as one of the 21 notes we have discussed

, find it and play it on the piano, and sing it back on wah.

REVIEW

The term "note" will be used to refer to a written musical symbol or the associated key on your keyboard, and the term "pitch" will be used to refer to a musical sound that is either played with your finger on a piano key, played on an instrument, or sung.

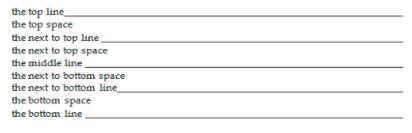

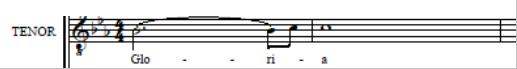

Look back at the tenor part presented on page 11 and presented again below. The five parallel horizontal lines in this example are called the staff. The staff is made of five lines and the four spaces between those lines. These lines and spaces can be described as follows:

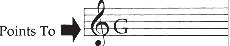

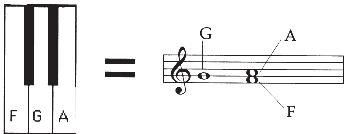

The clef is a sign found at the beginning of each staff. It points to one particular letter, or note-name, of the musical alphabet, and assigns one of the seven possible letters (ABCDEFG) to one particular line of the five lines of the staff. In the case of the G-clef featured below, the antique G encircles the next-to-bottom line and identifies noteheads appearing on that line as a "G."

FIG.16

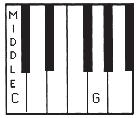

Whenever a black or hollow notehead appears on this line, the name of that note is the G above middle C on the keyboard.

FIG.17

This clef is also called the treble clef because the term treble

means high.

In the context of a chorus, it is used by the soprano section,

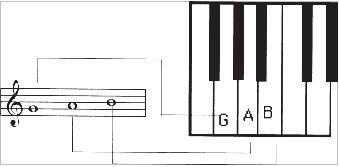

the alto section, and also the tenor section, which is the higher of the two male voice sections. Members of the tenor section have to learn that all of their notes need to be read down a full octave‐eight notes‐from where they were written. Notice the "8" under the G-clef in the tenor part presented again below that specifies this adjustment:

The musical alphabet ascends as you move from line to space or from space to line, and it descends as you move down from line to space, or from space to line. The clef points to the next to bottom line and designates it as a G, so the bottom space would be the letter beneath G in the musical alphabet, the letter F, and the space above the next to bottom line would be the letter above G in the musical alphabet, the letter A.

FIG.18

You already know about adjacent white keys on the piano and their relationship to adjacent letters in the musical alphabet. Now you can understand that these same adjacencies correlate with adjacencies on the staff, from space to line and from line to space.

You can now identify any other note in the written music by counting up or down from the line designating G find the corresponding white key on the piano.

FIG.19

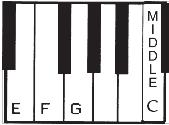

The other clef you need to learn is the F-clef, or bass clef, which is used for the bass section of the chorus.

This clef assigns the note to the on the next to top line of the staff. This is the F below middle C.

FIG.20

The relationships described on the previous pages in reference to the treble or G-clef remains the same with the bass of F-clef: As you move up and down the musical alphabet, you move from line to adjacent space, or from space to adjacent line.

There are mnemonic devices to help you remember how the note-names

line up on the staff. For example, the first letters of the words, Empty Garbage Before Dad Flips

correspond to the note-names as you move up the lines of the staff with the treble or G-clef in force‐EGBDF‐and F-A-C-E tells you the names of the ascending spaces. In the bass or

F-clef, "Good Boys Deserve Fudge Always" corresponds to the notes on the lines as you move from the bottom to the top.

While such devices are helpful at first, you will soon need to graduate from them to become fluent in this new skill of reading music.

You need to be able to identify note-names rapidly‐to look at notes presented on the staff and instantly convert them into letter-names. This is not necessarily interesting work but very necessary. You need to learn at the very outset of your study of music that notes belong in groups and in phrases, just like the words in a poem or a speech. But the work of naming individual notes is a necessary step to becoming a fluent music-reader, and is very similar to the task of the beginning language student, who must learn basic vocabulary before s/he can read sentences. If you find this work boring or annoying, do it in small increments of time, or do it with a friend or in a group, and trust that it will become "second nature" with time and practice.

To prepare for this new task, practice the two exercises presented below.

NOTE-READING EXERCISE 1

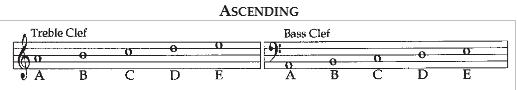

Learn to recite the musical alphabet in ascent. Notice that in the sequence of 7 ascending letter-names (or note-names), A follows G:

A-B-C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C-D-E...

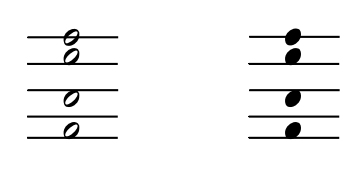

The sequence of letter-names corresponds with the note-names on the staff as they ascend by step from line to space, or from space to line.

FIG.21

NOTE-READING EXERCISE 2

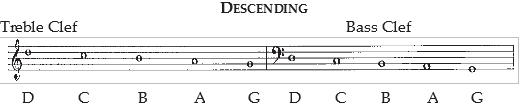

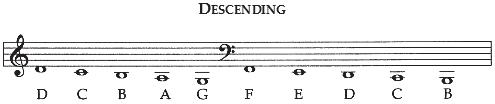

Learn to recite the musical alphabet in descent. Notice that G follows A.

G-F-E-D-C-B-A-G-F-E-D-C-B-A-G-F-E-D-C-B-A-G-F-E...

This sequence of letter-names corresponds with the note-names as they descend from line to space, or from space to line.

FIG.22

Ledger lines are used for even lower and higher notes:

FIG.23

Ledger lines can be thought of as continuing the five lines of the staff, and they are "read" in the same way as notes on the staff.

FIG.24a

FIG.24b

NOTE-NAMING EXERCISE 3

Sing ascending and descending note-names along with the piano within your vocal range.

Almost all the note-naming exercises that follow can be sung, and this is obviously preferable to merely speaking the names. You should try to sing in tune with your keyboard, and you should try to memorize how each pitch feels in your voice. Most people, however, particularly beginning musicians, are self-conscious about their singing and, until you have more confidence in your voice and your ability to read music, you may find it easier at first to speak and not sing the names of the notes.

FIG.25

By combining your ability to name notes in step-wise ascent or descent with your memorization of a few notes (e.g., the G in treble clef, the F in bass clef), you can now identify any note by counting by step from a line or a space that you do know.

This technique of using what you know to figure out something you do not know is called landmark identification

by music teachers. The comparison with the beginning language students is again useful: These students can often figure out the meaning of an unknown word by studying its relationship to the words that they already know.

Early in their training instrumentalists begin to associate certain aspects of their instrument with particular notes or groups of notes. For example, the beginning violinist learns the notes G, D, A and E because they

correspond with the open strings on the instrument. These notes become landmarks

for musicians‐notes that spring off the page because they are easily recognized and quickly converted into musical sound.

As a singer, you will also make connections between the musical notation and your voice. Notes at the bottom or top of your range may seem more difficult; notes in the middle of your range may seem easy in comparison.

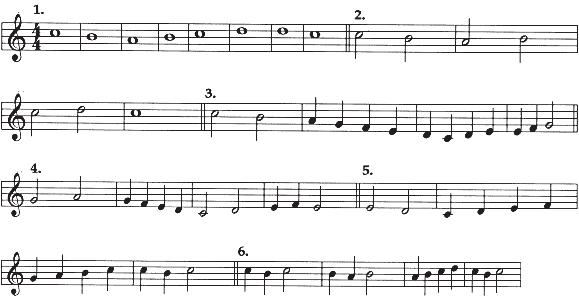

The text excerpt is perfectly suited for our present purpose. Every melody in that book was composed for the express purpose of providing introductory level music reading examples. You can begin to work through this text by naming or singing the noteheads on the first line.

The following information may be unnecessary for some, but I offer it here to make sure you understand the function of a notehead:

NOTE-READING EXERCISE 3

*This could also be practiced as if it were in bass clef by ignoring the G-clef and imagining an F-clef in its place.

Introduction to:

Melodia, A course in Sight-Singing/Solfeggio

by Samuel W. Cole and Leo R. Lewis

Published by Oliver Ditson Company, Theodore Presser Company

Notice that the notes follow one another in one of three ways:

Notice that the notes follow one another in one of three ways:

1. they move up by one letter-name (C-D, etc.)

2. they move down by one letter-name (C-B, etc.)

3. the same letter-name repeats (C-C, etc.)

For the time being, you do not need to worry about the difference between different looking notes‐these different durational values will discussed in the next volume.

You should, however, try to keep moving with some sort of beat, even if it is a very slow one. You can do this by tapping your hip as you work on speeding up your note-naming ability. Practice your note-reading on this exercise by naming the notes, singing the note-names, or playing the notes on your keyboard as you sing.

The note-naming you have done up to this point has been applied to melodies which only move up or down by step. The next exercises require you to skip intervening letter-names in the musical alphabet.

NOTE-READING EXERCISE 4

This exercise is not meant to be sung or played at the keyboard.

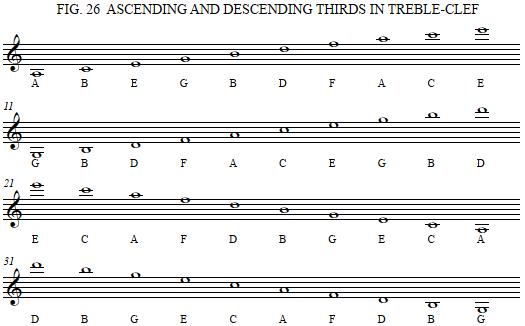

Memorize these two patterns: they repeat.

Ascent: A-C-E-G-B-D-F-A-C-E...

Descent: G-E-C-A-F-D-B-G-E-C...

These sequences of note-names can be described as ascending or descending by third.

Because any two adjacent notes within either of these sequences above involve three note‐the first note, the skipped note in the middle, and the last note‐they are said to be a third away

from each other. For example, the notes A to C are said to be a third

apart because their relationship involves three notes: the A(1), the B(2), which is skipped, and the C(3).

All the note-naming you have done up to this point involved notes which are a second apart.

For example, A-B involves two notes, A(1) and B(2). Therefore, they are a second apart.

Musicians do not usually use this means of describing this type of melody. Instead, this type of melody is described as moving by step or stepwise, or moving by scale or scalewise. You may have noticed already that every melody in the Melodia book moves only in this manner: The noteheads move either up or down or stay the same. But you will also discover eventually that the rhythms‐the various patterns of longer notes or shorter notes‐show a great deal of variety.

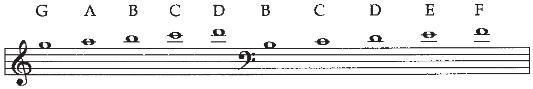

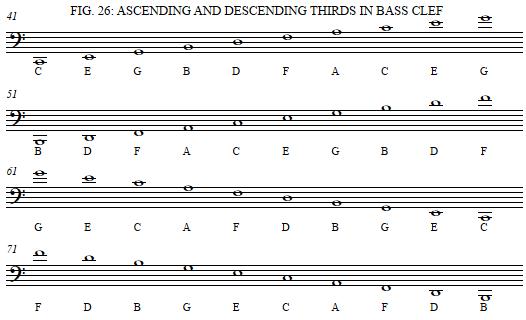

Sequences of note-names which either ascend or descend by third correspond to notes on the staff which are on adjacent lines or adjacent spaces. See figure 24 below.

FIG.26

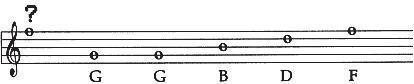

Once you are able to ascend or descend by third through the musical alphabet, you can apply this skill to situations where you do not immediately recognize a note-name. By locating a landmark note, that is, a note that you do know, you can move quickly up or down by third and recognize the note you don't know. For example, if you are confronted by the note on the top line in the treble clef, you can start from the G on the next-to-bottom line and spell up three successive thirds ‐ G-B, B-D, D-F ‐ to find the F on the top line.

FIG.27

Using all the information and techniques offered so far, you should now be able to identify any note in either bass or treble clef fairly quickly. Remember that your aim is to eventually wean yourself from these supports and mnemonic aids. Ideally, every note will eventually seem like a landmark note after you have mastered both clefs. As you do this identification work, keep this last point in mind: always attempt to memorize the names of notes you cannot immediately identify. If you do not make this extra effort, you might remain dependent on the methods that were useful to you at first but now need to be filed in the back of your thinking in case you need to call on them in the future.

If you force yourself to memorize one or two new notes each time you practice, you will more quickly achieve note-naming fluency in both treble and bass clefs. Use whichever method you find helpful in this process: how the note appears on the staff, how the note feels in your throat as you sing it, how it looks on the piano, how it is fingered on the guitar, etc. Any associations you can make with a particular note or group of notes can be useful at this point.

Being able to name notes is only the first step towards the music- reading fluency you seek: there is more to reading music competently and expressively than just being able to name notes. If we converted this level of fluency in note-reading to language study, we would hear a young man from another country reading a Shakespeare sonnet word.........to.........word...., with........ many......... hesitations........ and....... with......... no........ value......or......emphasis.......on...any...one. word.

In this situation the vocabulary is being recognized, but there is no awareness of how the meaning of a sentence should be communicated by the flowing combination of words. On the other hand, the ability to name notes‐like recognizing vocabulary‐is a foundational skill that is essential to more advanced skill acquisition.

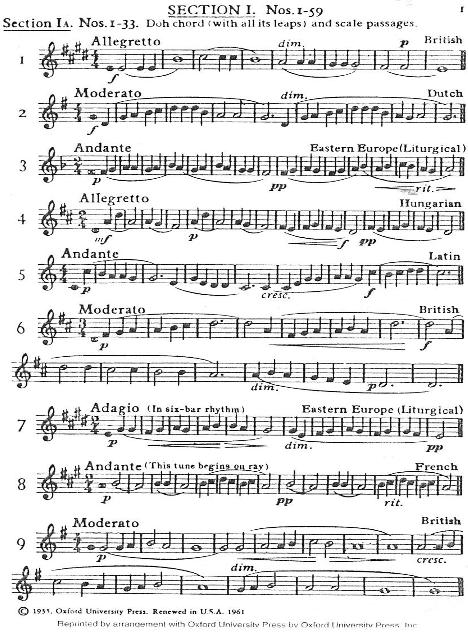

Introduction to:

The Folk Song Sight Singing Series, Book I

Compiled and edited by Edgar Crowe, Annie Lawton, W. Gilles Whittaker

Oxford University Press

This music book will be useful at this point because it will provide you with note-naming exercises that are more difficult than the exercises we encountered in Melodia.

The note-to-note motion in these melodies does not always proceed stepwise; and these melodies include larger skips than thirds, as well.

NOTE-READING EXERCISE 5

This exercise is not meant to be sung or played at the keyboard.

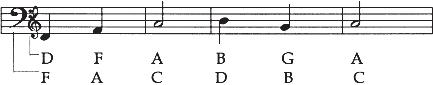

Look at Figure 26 below and name the notes as quickly as you can. For now, ignore the graphic information you don't understand.

FIG.28

The first melody is presented again below in Exercise 9, although it is now presented in the bass clef. Name these notes as well. By ignoring the clef sign in the Oxford book and pretending that all of these melodies were written in bass clef, you can use this book of melodies to develop note-reading ability in both treble and bass clefs.

NOTE-READING EXERCISE 6

This exercise is not meant to be sung or played at the keyboard.

NOTE-READING EXERCISE 7

This exercise is not meant to be sung or played at the keyboard.

Name these notes in G- and F-clefs.

Proceed through the nine melodies in the Oxford text until this becomes easy. Practice naming notes in treble and bass clefs. As prescribed earlier, keep a steady pulse when you do this note-name identification work. It is better to skip a note you do not know and keep a consistent tempo. If you are forced to do this, return to the note later that you had to skip and concentrate on it. Turn it into a landmark note by fastening it somehow in your memory with some aspect you notice about it. Feel free to do this identification work by singing the names of the notes as you play them on your keyboard, but understand that the focus of this work is on learning to name notes.

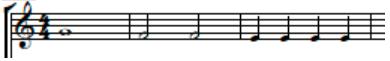

The last exercise in note-naming involves notes that are spread randomly all over the staff. You have followed a training sequence by first mastering exercises in which all notes related to each other by step (Melodia); you then mastered exercises with skips between notes (Oxford Folk Song Sight- Singing Series.) Now you are ready to confront more difficult distributions of notes which are presented below in both treble and bass clefs.

NOTE-READING EXERCISE 7

This exercise is not meant to be sung or played at the keyboard.

Name these notes in both G- and F-clefs.

THE INFAMOUS 60-SECOND SHEET

You may have more trouble with the notes above and below the staff, and you can skip these notes at first. Circle them and try to memorize a new one each practice session. You may also decide to learn only the clef you will use most as a singer or an instrumentalist, but this will limit your ability to converse with your keyboard accompanist who plays in both clefs.

Again, it is best to identify these notes in a steady pulse‐drop out the difficult notes and continue with the notes you know. Again, do not try to sing this sheet: some of the pitches will be out of your vocal range and the large skips between notes within your range would be difficult for even the most advanced music reader. Also, this exercise is not music; it was designed only to test your mastery of note-reading.

This is dry and demanding work, partially because it has removed the musical sound and focused on the skill-building in order to accelerate the learning process. Take heart in the fact that every musician can find a speed at which this type of task becomes impossible. You have already built significant skill with note-reading, so take pride in what you have learned so far! Hopefully, you will find that this work was worth the effort.

When you feel ready, begin Volume 2, in which every exercise can be played at the piano and sung!

Steve Peisch, July, 2020